Author’s Note – For more information about Dr. Eugenie Clark and her work with lemon sharks, click here.

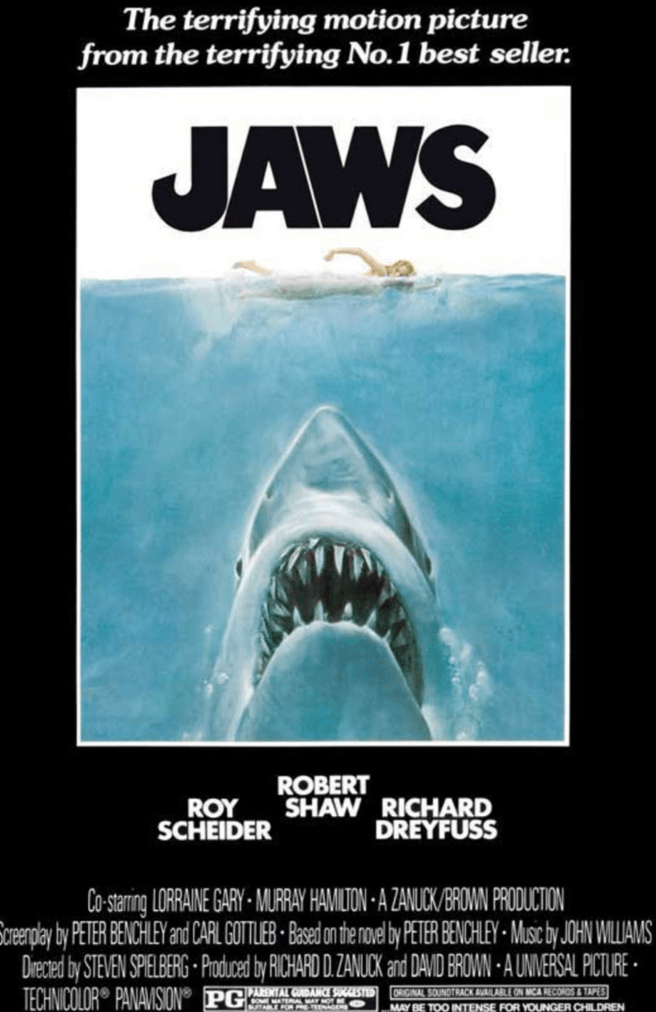

“That’s one of the things I still fear. Not to get eaten by a shark, but that sharks are somehow mad at me. I truly and to this day regret the decimation of the shark population because of the book and film. I really, truly regret that.” —–Stephen Spielberg

The last time I vacationed on Hilton Head Island, conditions were ripe for an influx of stingrays – the water was calm, warm and (since Hilton Head is a barrier island) shallow enough to be a haven for them. They weren’t especially dangerous but stepping on one’s tail would make you sick enough to ruin your vacation. Locals will tell you that shuffling your feet as you near the water’s edge will scare them off, but the only thing that truly made me feel better was the first lemon shark sighting later that week. Why? Because lemon sharks have a voracious appetite for stingrays, so much so that marine biologists have done necropsies on lemon sharks only to find they choked to death on stingray barbs. I had recently ready about Dr. Eugenie Clark and her pioneering work with these fish that proved their intelligence and docility, and I tried my best to convince my fellow tourists that they were safe. I tried to teach them that sharks were only there to eat the stingrays, but I’m not sure I made much of an impact.

The truth is, sharks have much more to fear from us than we do from even the biggest of their kind. According to Science News, out of all the millions of people who swim in the ocean each year, there are only, on average, 64 shark attacks. Of that number, less than 9% are fatal. Since the mid-1970’s, shark and ray populations have declined by 70% and about 1/3 of both species are on the verge of extinction. Of the 1250+ species recognized by the IUCN, 90% have been victimized by overfishing, whether by accident (bycatch and ghost gear entanglements) or as a deliberate act (finning). Sharks don’t get much publicity unless someone is a victim of an attack, and apathy and fear keeps people from fighting to protect them — unless we change our perspective on these enigmatic apex predators, things will only get worse for them.

Sharks are a class of fish called chondrichthyans, which means their skeletons are made of cartilage and they range in size from the length of a bowling alley lane (whale shark) to ones only a few inches long (dwarf lanternsharks). They have existed in more or less the same form for over 400 million years and have unbelievable lifespans; the Greenland shark is the world’s longest lived vertebrate, with an average lifespan of 270 years. Females don’t breed until they are about 150 years old, which creates a unique dilemma: sharks can’t reproduce fast enough to keep up with how quickly we keep killing them. Indonesia, India and Spain account for 35% of all sharks killed worldwide, and only about 1/4 of these sharks are intentionally caught. Even so, the demand for shark and ray meat as a protein source has doubled in the past twenty years as other seafood sources are being depleted. Shark fishing can be sustainable, however, and is not the leading cause of their decline. That ignominious title goes to a meal that is considered a delicacy in many parts of Asia – shark fin soup.

Although the soup has existed as a symbol of wealth and decadence since the Ming Dynasty, a recent surge in the middle class population has increased demand for it. Fins can bring in up to $450 a pound and a single bowl of soup can sell for as much as $100 in a gourmet restaurant. Sharks are routinely caught, their dorsal fins are hacked off, and then they are thrown overboard. If they survive the initial trauma, they can’t survive without their dorsal fins because they can’t breathe (not all sharks have to move to breathe but many do), bleed to death or are easy prey for other sharks because they can’t swim. In 2006, NBA superstar Yao Ming teamed with WildAid to educate people on the impact harvesting fins has on sharks. At the start of the campaign, 3/4 of Chinese people didn’t know what shark fin soup was made of, as the Mandarin name translates to “fish wing soup”. 19% also believed that sharks could grow their fins back. The campaign slogan was “when the buying stops, the killing can too” – as a result, 89% of people polled said finning was inhumane and should be banned, and in 2019 it finally was.

Another danger to shark populations is sport fishing, and catch-and-release tournaments have the most negative impact. When sharks are reeled in and landed on a boat deck, they can suffer internal injuries and vertebral damage, or worse. Hammerheads almost always die when caught, and pregnant sharks will either give birth prematurely or suffer miscarriages – all so that fisherman can have the opportunity for photo ops and bragging rights. French Polynesia banned these competitions in 2006 but they sill take the lives of too many sharks each year.

My one and only truly close encounter with a shark was on that same beach trip – I came across some men fishing in the surf when I was taking a walk. They caught a small shark not much bigger than the palm of my hand. When they showed it to me, I touched it and was surprised to learn it felt like sandpaper. There was nothing frightening about this creature and I felt terrible when I saw the guys put it in a bucket of salt water instead of releasing it. I didn’t say anything but now a part of me wishes I had. We all need to say something. Education matters – we can’t save sharks if we don’t try to help others understand them and the world they live in. We don’t need a bigger boat. We need a bigger heart.

Sources:

Randall, Brianna. “Save the Sharks” Science News, July 2025 pp 35-39

“What is Shark Finning?” http://www.sharkallies.org/oceans-knowledgebase/what-is-shark-finning 6/1/25

“What Is Shark Fin Soup?” http://www.sharkallies.org/oceans-knowledgebase/what-is-shark-fin-soup 6/2/25